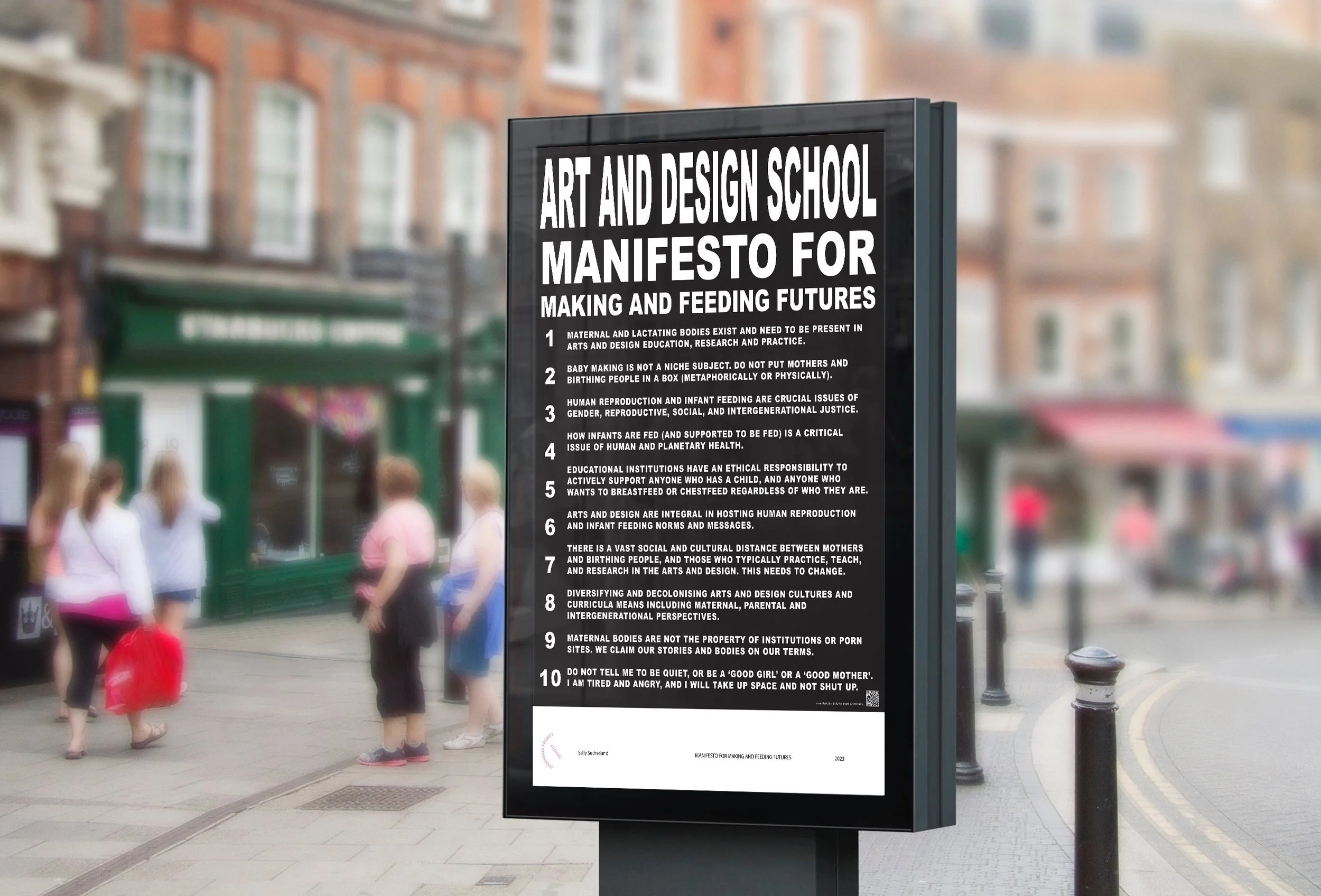

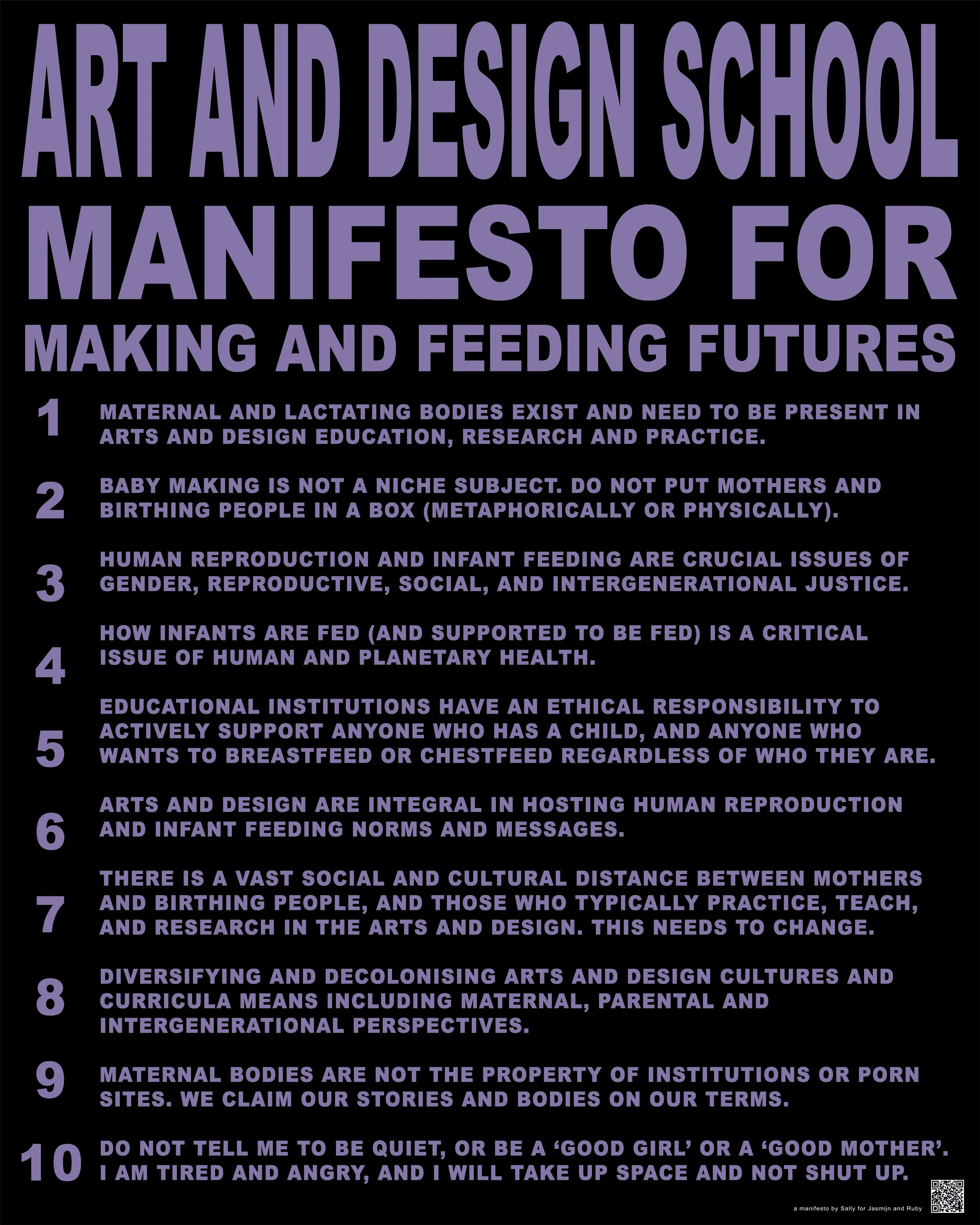

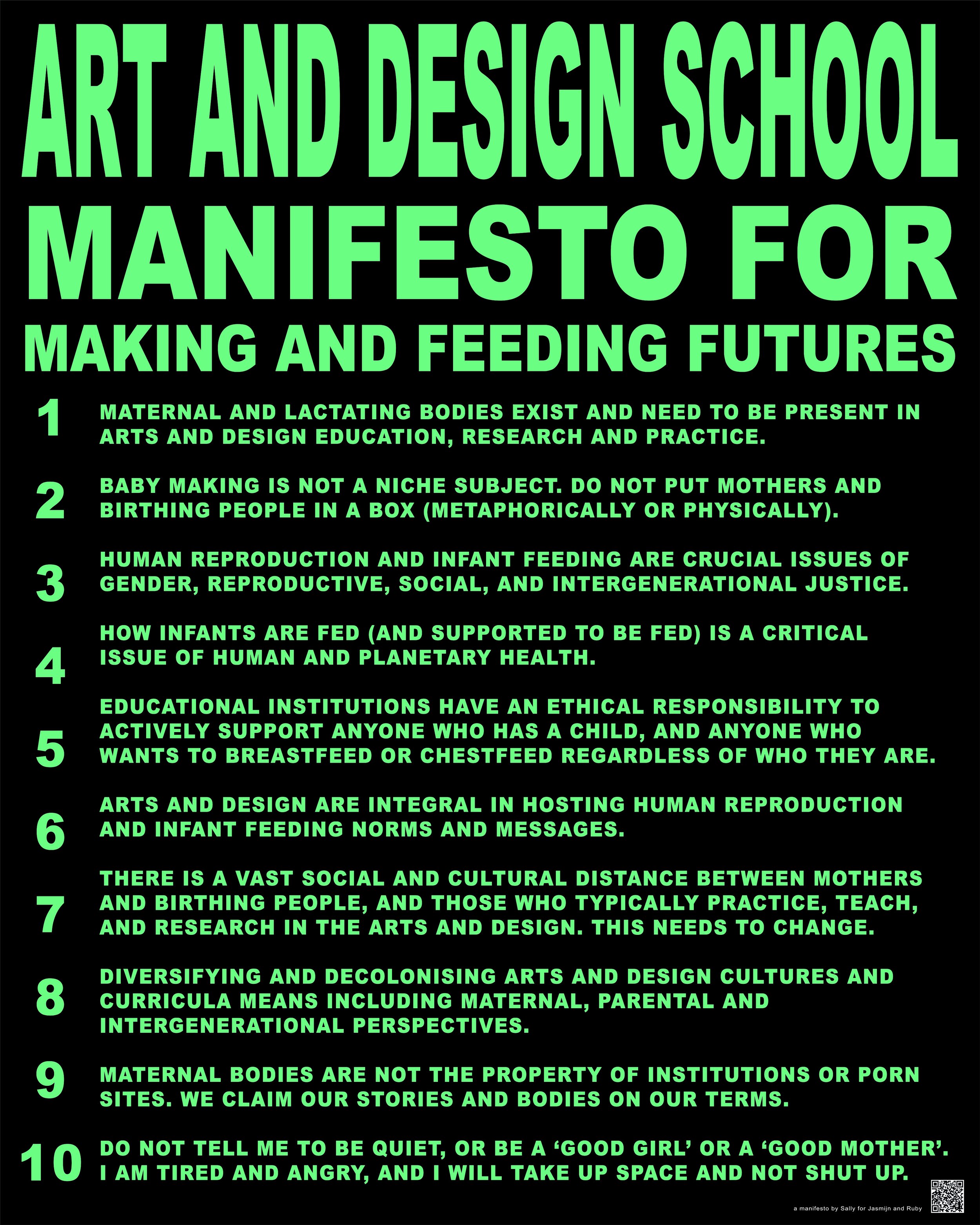

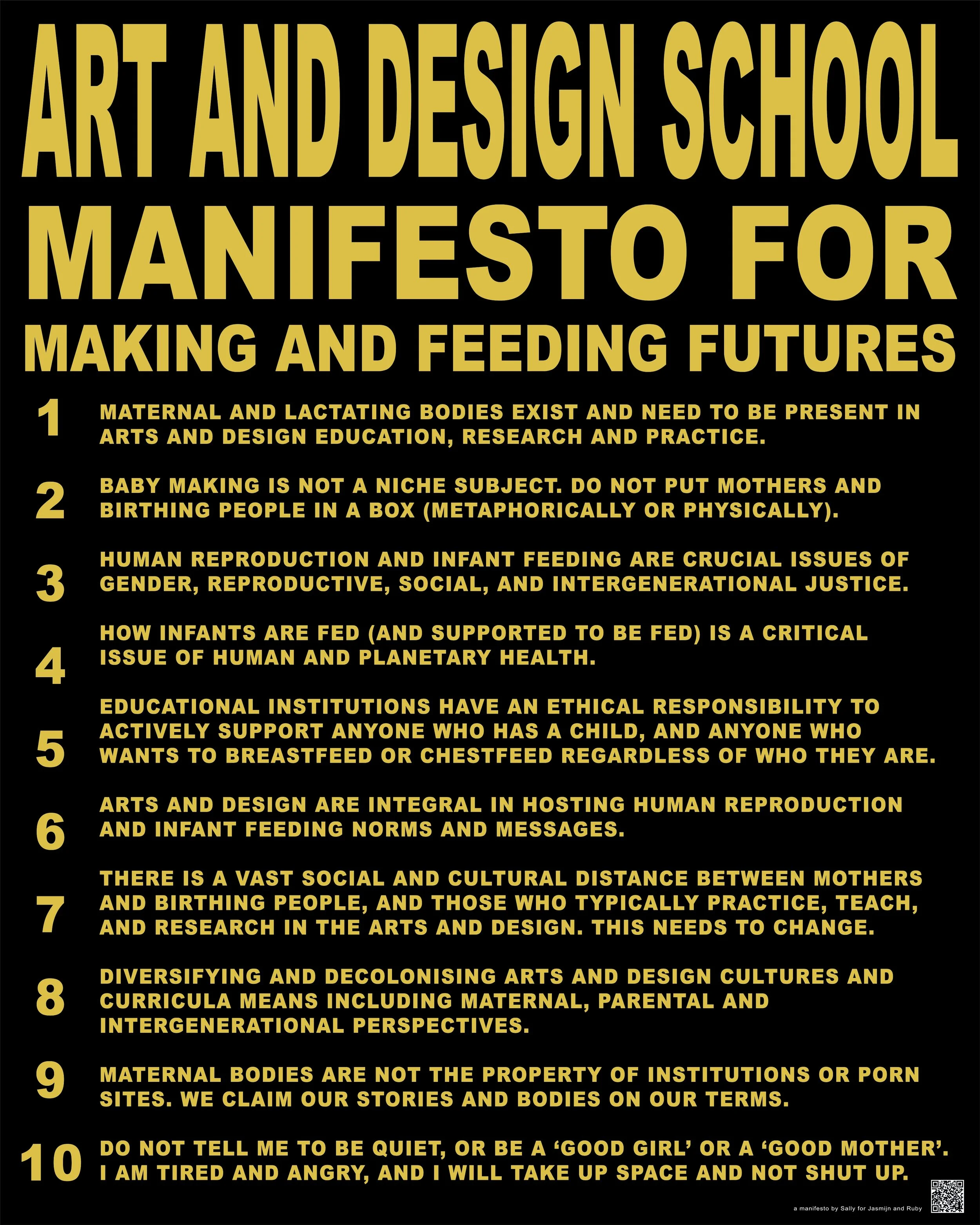

ART AND DESIGN SCHOOL MANIFESTO FOR MAKING AND FEEDING FUTURES

ART AND DESIGN SCHOOL MANIFESTO FOR MAKING AND FEEDING FUTURES

baby change-making - exhibition - event - talk - Central Saint Martins - March 2023 -

baby change-making - exhibition - event - talk - Central Saint Martins - March 2023 -

Making space for the maternal and parental voice in design education and research.

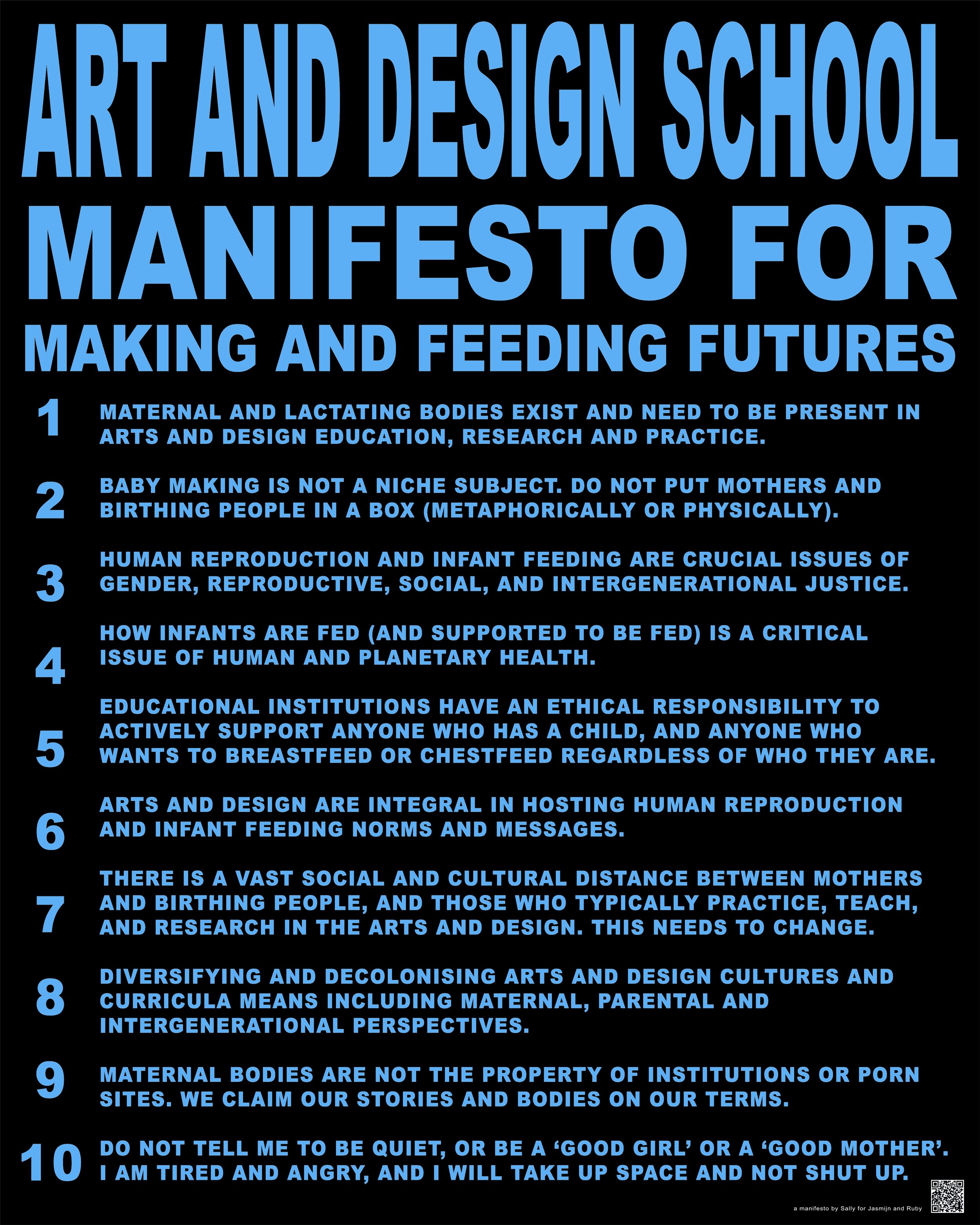

This manifesto was created for an exhibition at Central Saint Martins, UAL in March 2023 for a project called Baby Change Making about making change for mothers and parents in higher art and design school education. The exhibition and event is curated by BA Graphic Communication Design students Jasmijn Toffano and Ruby Gamman Wragg.

The manifesto has so far been exhibited at Brighton CCA, Hastings Contemporary, Central Saint Martins, UAL, and presented at the UK Houses of Parliament..

DOWNLOAD POSTER

DOWNLOAD POSTER

The poster is available to download for free from the Procreate Project Archive.

Houses of Parliament Presentation

Together with Jasmijn and Ruby, I was invited to present ‘Infant Feeding and baby making in Arts and Design education, research and practice’ at the Houses of Parliament. The presentation was to the APPG (All Party Parliamentary Group) on Infant Feeding and Inequalities, chaired by Alison Thewliss MP and took place on 14th March 2023. The presentation was part of the Baby Change Making project about making change for mothers and parents in higher art and design school education.

left to right. Sally Sutherland, Jasmijn Toffano, Ruby Gamman Wragg, Alison Thewliss MP

1. Maternal and lactating bodies exist and need to be present in arts and design education, research, and practice.

Erasing or restricting maternal and lactating bodies from art and design education, research, and practice is a form of gender-based violence. Art and design disciplines must stop contributing to the motherhood penalty,[1]and confront their legacies of oppression. These legacies include the consistent side lining and undervaluing of maternal narratives in art and design disciplines.[2]

Research and practice in art and design critique and make sense of experiences, including evolving technological landscapes. Among contemporary technologies, an increasing number of reproductive technologies affect how people are born, cared for and fed. These include technologies to delay parenthood, artificial human milks, milk pumping devices and child monitoring technologies often developed to ‘fix’ perceived problems. Designers also shape how motherhood, parenthood, and childhood are communicated and experienced in the world. Maternal and gestational parent perspectives are therefore essential in this work, without which maternal and lactating bodies can be sidelined and further oppressed.

2. Baby making is not a niche subject. Do not put mothers and birthing people in a box (metaphorically or physically).

Having a baby, being born, feeding, or being fed is extraordinarily ordinary. Please do not ‘other’ mothers and birthing people. Please do not ‘other’ babies and infants. There is no one way to mother or parent, be born, fed, or be a child. There are as many different types of mothers, parents, and children as there are people in our world. Do not put me in boxes, in white windowless rooms,[3] or tell me what to do, feel, make, learn, or wear.[4] Do not tell me where to go or when.

3. Infant feeding is an issue of gender, reproductive, social, and intergenerational justice.

Issues of reproduction and infant feeding are not solely women's issues. These issues affect people of all genders. However, mothers and parents with marginalised gender identities are disadvantaged most by UK norms. As reproduction, breastfeeding, and chestfeeding connect to both biological sex differences and gender roles and expectations, this is essential to clarify due to the current violent conflicts about gender inclusivity in the UK birth world. Including people of all gender identities in infant feeding discourses is a matter of reproductive justice. The right to choose how and when to have children, to parent, to feed, and to do this in safe communities are all reproductive justice issues.[5] It is well established that supporting breastfeeding helps reduce lifelong health inequalities for all people involved.[6] Correspondingly, not providing adequate access and systemic support to breastfeeding or chestfeeding can perpetuate growing UK social and intergenerational inequalities.

4. How infants are fed (and supported to be fed) is a critical issue of human and planetary health.

The individual health benefits of breastfeeding are well-documented. Something less documented and discussed is how not supporting breastfeeding and chestfeeding leads to environmental and ecological displaced harms that affect people, climate, ecological and environmental systems in distinctly different parts of the world from where individual feeding 'practices' are often occurring.[7] The last UK-wide Infant Feeding Survey showed that eight out of ten are women stopping breastfeeding before they want to.[8]On an individual level, therefore, there is a collective infant feeding want, but this does not come with collective cultural or institutional support. Therefore, there is a responsibility to acknowledge infant feeding as not solely connected to individual health but to global issues of planetary health. Institutional leaders and policymakers need to more directly and explicitly acknowledge this by including breastfeeding and chestfeeding support in broader sustainability agendas.

5. Educational institutions have an ethical responsibility to actively support anyone who has a child, and anyone who wants to breastfeed or chestfeed, regardless of who they are.

UK public health messaging encouraging new mothers and birthing people to exclusively breastfeed or chestfeed their children. However, parents and infants are surrounded by a systemic and cultural lack of support to do so.[9] British culture could be supportive of breastfeeding or chestfeeding practices – but it is not. UK breastfeeding rates remain among the lowest in world.[10] Educational institutions are foundational to British culture and play an influential role in shaping norms and expectations of young people. How these norms and expectations are generated and reproduced is shaped by the inhabitants and leaders of the institutions. These leaders, therefore, have a responsibility to actively attend to who is included and excluded from these opportunities and spaces and take responsibility for the consequences of these actions.

6. Arts and design are integral in hosting human reproduction and infant feeding norms and messages.

Infant formula feeding norms and related messages are embedded within spaces, objects, systems, and structures. These embedded messages in artifacts impact how women, parents, and infants can or cannot negotiate infant feeding 'choices'.[11] These largely invisible but highly significant impacts are rarely discussed, despite insidiously affecting infraordinary everyday lives, lifelong human health inequities and planetary health. Mothers and birthing people need to be involved in making and expanding these spaces, objects, systems, and structures. This means attending to maternal and parental voices in design, and unrestricted and supported access to arts and design education, research, and practice.

7. There is a vast social and cultural distance between mothers and birthing people, and those who typically practice, teach, and research in the arts and design. This needs to change.

This distance is especially vast when considering mothers and birthing people with intersecting marginalised identities, including race and class. The results are a population living with the consequences of well-meaning but ill-informed solutions or responses to situations that do not reflect most lived realities. Not adequately supporting student, educator, and creative practitioner mothers and parents to breastfeed or chestfeed contributes to perpetuating inequalities in opportunities. Supporting mothers and birthing people in their teaching and research careers and not penalising these people because of their caring responsibilities within the arts and design education sector is critical.

8. Diversifying and decolonising arts and design cultures and curricula means including maternal, parental, and intergenerational perspectives.

Arts and design education, research and practice are at a critical point of challenging where our knowledge making and creative practice comes from, and who chooses. Mothers and birthing people are a part of this. Attending to diversity and decolonisation means acknowledging and prioritising historically silenced perspectives, inclusive of mothers, birthing people, and children.

9. Maternal bodies are not the property of institutions or porn sites. We claim our stories and bodies on our terms.

You do not choose what I do and how I do it. In the UK, I am legally allowed to breastfeed or chestfeed anywhere, yet this is not the story told by UK culture and media. Arts and design practices have a fundamental role to play in how and where stories are told and by whom. Creative practice can play a part in challenging and reclaiming narratives about maternal, lactating, and birthing bodies. Telling new stories is one of our superpowers as creative practitioners. Art and design schools and research can play an active role in making and telling stories to perform resistance and speculate on alternative futures.

10. Do not tell me to be quiet or be a ‘good girl’, or a ‘good mother’. I am tired and angry, and I will take up space, and not shut up.[12]

Care is not cuddly,[13] intimate caring practices can be sacred, messy, and labour-intensive. Zoom meetings and home-schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns highlighted how maternal or parental care cannot be easily tidied away or walked away from. It is twentyfourseven. My own caring practices are simultaneously my greatest privilege and biggest trap— the source of the most pleasure and deepest pains. Mathilda Tham reminds me that a big challenge to overcome comes from being told to 'be a good girl'.[14] To make change, I must make a fuss. Systemic change must happen at all levels, and we can make change together. Our arts and design practices make our everyday lives – education is power.

Action is needed to tackle inequalities in health in a post-pandemic world.[15] Addressing multilevel barriers to breastfeeding and chestfeeding need to be implemented to enable healthy, equalizing, and sustainable infant feeding practices.[16] Every sector and discipline has a part to play. This manifesto articulates why this is important and suggests how Art and Design Schools can respond and act.

References

Beard, Mary. Women & power: A manifesto. Profile Books, 2017.

Brearley, J., (2022) The Motherhood Penalty: How to stop motherhood being the kiss of death for your career, Simon & Schuster UK

Brown, Amy. Breastfeeding uncovered: Who really decides how we feed our babies? Pinter & Martin, 2021.

Dahlgren, Göran and Margaret Whitehead. "The Dahlgren-Whitehead Model of Health Determinants: 30 Years on and Still Chasing Rainbows." Public Health (London) 199, (2021): 20-24.

Fisher, Michelle Millar, and Amber Winick. Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births. MIT Press, 2021.

McAndrew, Fiona, Jane Thompson, Lydia Fellows, Alice Large, Mark Speed, and Mary J. Renfrew. "Infant feeding survey 2010." Leeds: health and social care information Centre 2, no. 1 (2012).

Pérez-Escamilla, Rafael, Cecília Tomori, Sonia Hernández-Cordero, Phillip Baker, Aluisio J. D. Barros, France Bégin, Donna J. Chapman, et al. "Breastfeeding: Crucially Important, but Increasingly Challenged in a Market-Driven World." The Lancet (British Edition) 401, no. 10375 (2023): 472-485.

SisterSong. “Reproductive Justice,” sistersong.net. https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice (accessed 01 March 2023).

Sutherland, Sally. (2022) Leaky Systems: Infant feeding and design. In Proceedings of Relating Systems Thinking and Design (RSD11) 2022. Brighton, UK, October 13-16, 2022.

Sutherland, S. (2023) Chapter 15: Sexual and street harassment. In M. Rogers, & P. Ali (Eds.), A Comprehensive Guide to Gender-Based Violence Springer. (forthcoming).

Tham, M. “Wicked possibilities.” Pre-recorded presentation for Wicked Possibilities: Designing in and with systemic complexity [webinar], University of Brighton, UK, July 15, 2020. Available at https://vimeo.com/436882571

Tham, M. “Wicked possibilities.” Presentation at Wicked Possibilities: Designing in and with systemic complexity [webinar], University of Brighton, UK, July 15, 2020. Available at https://vimeo.com/466236425

Victora, Cesar G., Rajiv Bahl, Aluísio JD Barros, Giovanny VA França, Susan Horton, Julia Krasevec, Simon Murch et al. "Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect." The lancet 387, no. 10017 (2016): 475-490.

[1] For more information on The Motherhood Penalty, I recommend Joeli Brearley’s 2022 book. However, I believe all mother or parent, child caring practices to be work. The concept of ‘the working mum’ used by Brearley is therefore problematic. Whether you are studying, caring for your child or someone else, in paid or voluntary employment, you are working. If you are doing two, or more, as many people were in lockdown, you are working ALOT.

[2] Fisher, Michelle Millar, and Amber Winick. Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births. MIT Press, 2021, p.16

[3] This is a nod to the white windowless rooms where breastfeeding and chestfeeding people are frequently asked to feed their infants or pump breastmilk.

[4] In reference to the often-harmful baby care books (Amy Brown discusses this well in her book Breastfeeding Uncovered), and online social media presence of influencers telling mothers and birthing people what to do.

[5] SisterSong, the Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective defines Reproductive Justice as “the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities”. “Reproductive Justice,” SisterSong, https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice (accessed 01 March 2023).

[6] Victora, Cesar G., Rajiv Bahl, Aluísio JD Barros, Giovanny VA França, Susan Horton, Julia Krasevec, Simon Murch et al. "Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect." The lancet 387, no. 10017 (2016): 475-490.

[7] Sutherland, Sally. (2022) Leaky Systems: Infant feeding and design. Relating Systems Thinking and Design (RSD11) 2022. Brighton, UK, October 13-16, 2022.

[8] McAndrew, Fiona, Jane Thompson, Lydia Fellows, Alice Large, Mark Speed, and Mary J. Renfrew. "Infant feeding survey 2010." Leeds: health and social care information Centre 2, no. 1 (2012).

[9] Brown, A. (2021). Breastfeeding uncovered: Who really decides how we feed our babies? Pinter & Martin.

[10] McAndrew, Fiona, Jane Thompson, Lydia Fellows, Alice Large, Mark Speed, and Mary J. Renfrew. "Infant feeding survey 2010." Leeds: health and social care information Centre 2, no. 1 (2012).

[11] Sutherland, S. (2023) Chapter 15: Sexual and street harassment. In M. Rogers, & P. Ali (Eds.), A Comprehensive Guide to Gender-Based Violence Springer. (forthcoming).

[12] In reference to Mary Beards ideas on speaking in public and not shutting up. Beard, Mary. Women & power: A manifesto. Profile Books, 2017, p.45

[13] Tham, M. “Wicked possibilities.” Pre-recorded presentation for Wicked Possibilities: Designing in and with systemic complexity [webinar], University of Brighton, UK, July 15, 2020. Available at https://vimeo.com/436882571

[14] Tham, M. “Wicked possibilities.” Presentation at Wicked Possibilities: Designing in and with systemic complexity [webinar], University of Brighton, UK, July 15, 2020. Available at https://vimeo.com/466236425

[15] Göran Dahlgren and Margaret Whitehead. "The Dahlgren-Whitehead Model of Health Determinants: 30 Years on and Still Chasing Rainbows." Public Health(London) 199, (2021):23

[16] Rafael Pérez-Escamilla, Cecília Tomori, Sonia Hernández-Cordero, Phillip Baker, Aluisio J. D. Barros, France Bégin, Donna J. Chapman, et al. "Breastfeeding: Crucially Important, but Increasingly Challenged in a Market-Driven World." The Lancet (British Edition) 401, no. 10375 (2023): 481

Photos below show the Manifesto on display at the Tetley Gallery, in Leeds for Leeds Baby Week. The manifesto was redesigned by Textbook Studio, for Gallery 4. This is part of the Feed Project, by In Certain Places. Photos by Fiona Finchett